How to Make Your Mother Proud

History is rife with examples of women who effected change, then vanished into obscurity. When it comes to the story of how the 19th Amendment became a reality—irony be damned—it’s no different.

In downtown Knoxville, Tenn., on the corner of Clinch Avenue and Market Square, a stone’s throw from what used to be the federal courthouse, a statue of a man and a woman will occasionally attract the attention of a curious pedestrian.

The man is sitting on a chair, his posture relaxed. He’s clad in a suit and tie. The woman stands next to him, one of her hands perched, somewhat protectively, on his shoulder; the other clasping a small bouquet of flowers. Both share a look of stern resolve.

Her name is Febb. His name is Harry. A mother and son who together, 104 years ago this month, changed American history.

Febb—or Phoebe Ensminger Burn—was a woman ahead of her time. She was born in 1873 near Niota, Tenn., but little is known about her childhood. What we do know is that she graduated from U.S. Grant Memorial University—now Tennessee Wesleyan—at a time when academia was a man’s domain and not something to be squandered on the meek minds of the fairer sex.

She read vociferously—three newspapers a day, by some accounts—and harbored a deep and constant resentment about the fact that society considered her intellect and opinions to be inferior to those of a man.

As a young woman, despite being well-versed in the political feuds and international relations of the day, Febb didn’t have the right to vote.

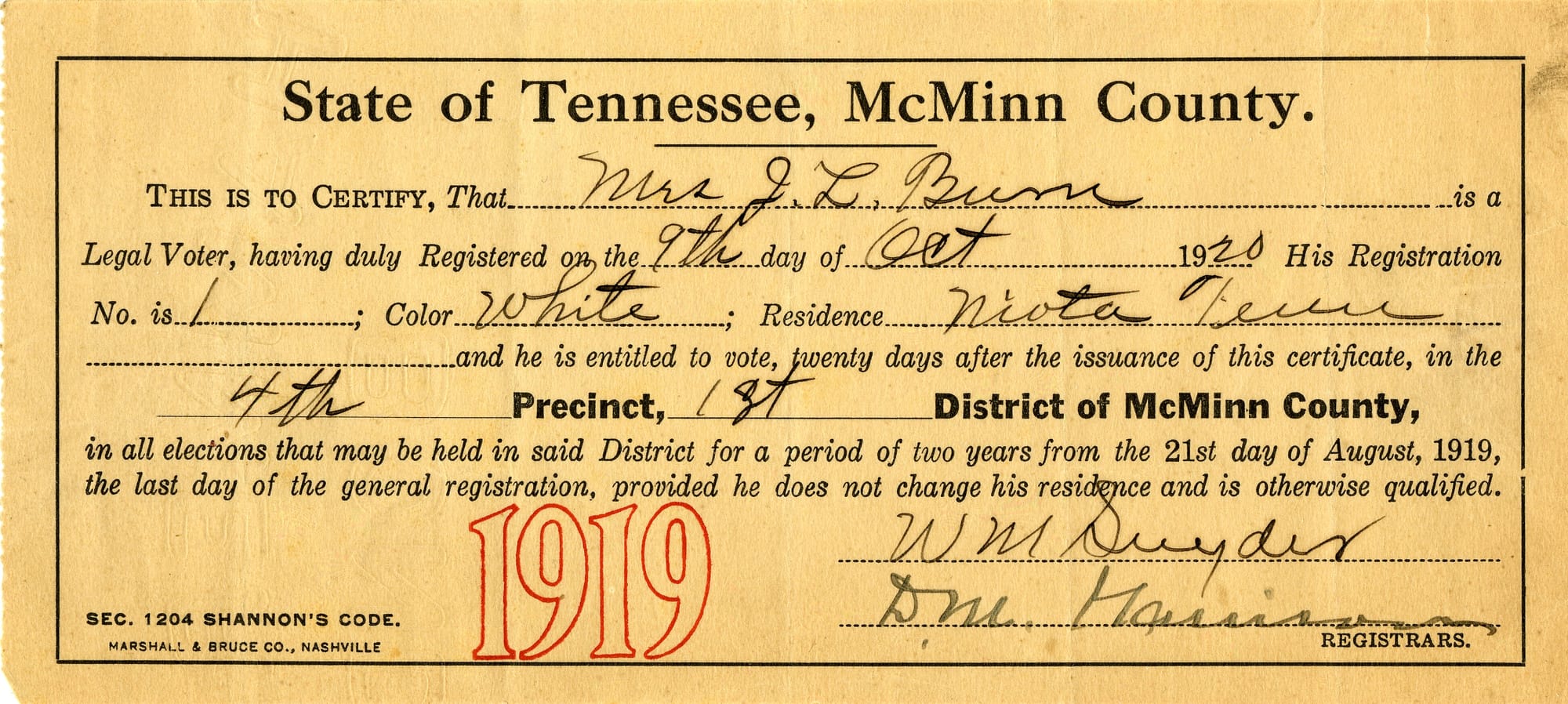

After college, she worked as a teacher and married James Lafayette Burn, a stationmaster. Together the pair ran the family farm and had four children, but in 1916 James died of typhoid fever, leaving Febb to raise three of their children alone. A daughter, Sara, had died two years earlier.

Mourning the losses, Febb dedicated her life to being a homemaker and raising children. But it wasn’t just any child she was raising. For it was her oldest son Harry T. Burn—immortalized by the Burn Memorial in a buzzy part of Knoxville—who would end up casting the deciding vote that led to the ratification of the 19th Amendment, ending suffragists’ long crusade that won women the right to vote.

Obscured by History

History is rife with examples of women who effected change and then vanished into obscurity, and when it comes to the story of how the 19th Amendment became a reality—irony be damned—it’s no different.

Even Alice Paul, the author of the first iterations of the eventually-thwarted Equal Rights Amendment—and arguably one of U.S. history’s most ardent advocates for gender equality and suffrage—is far from a household name (unless that household has seen the Tony-award winning musical Suffs, in which case she is a household name).

There was also Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. There was Lucy Stone and Lucy Burns. There was Crystal Eastman and Carrie Chapman Catt and Inez Milholland and Doris Stevens and Mary Church Terrell and Hallie Quinn Brown and Charlotte Hawkins Brown and, of course, Ida B. Wells. And yes, some of these names might ring a bell—might conjure up the hazy memory of an old high school history lesson—but most likely won’t.

As for Febb Burn? At the time of this writing, the woman who arguably instigated one of the most important votes in the history of the U.S., hasn’t even been granted the dignity of a Wikipedia page.

A Seven-Decade Battle

Because Febb’s life was written into history almost entirely in the context of her son, information about who she was is scant. Information on the impact of her actions, however, is not.

On August 18, 1920, the Tennessee legislature—all men, of course—was on the cusp of deciding whether to ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution—which would give most (but not all) women the right to vote. To say that the day had been a long time coming would be an epic understatement. Suffragists had been advocating for the Amendment for more than 70 years, bruised, but never deterred.

On March 3, 1913, for example, the eve of president-elect Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration, the suffragists staged a massive women’s march for nationwide suffrage in Washington, D.C. Crowds of outraged onlookers—mostly men—attacked the parading women, bringing the event to an end, but the march drew extensive media coverage, and introduced the idea of voting rights into mainstream conversation.

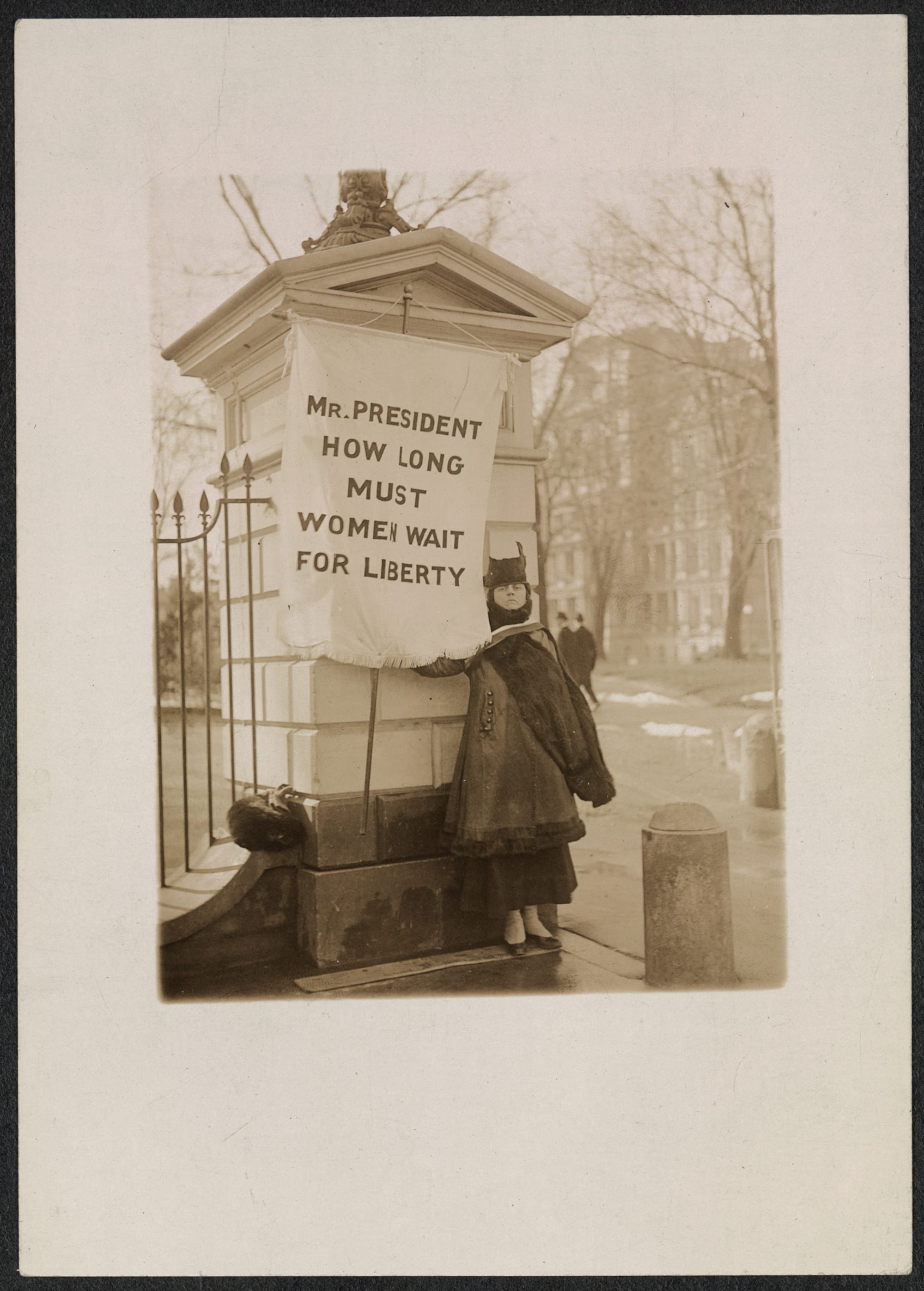

'Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?'

Four years later, the National Woman’s Party organized the first-ever public picketing in front of the White House to demand the vote. So-called Silent Sentinels bearing protest banners stood outside the gates of the White House to shame President Wilson for his inaction and apathy on the cause of women’s rights. “Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” one banner read.

Alice Paul, a leader of the picketing, was eventually arrested and locked up, but after a hunger strike she was released. Not long afterwards, Wilson began to soften his stance. In a 1918 speech before Congress, the president finally publicly endorsed women's suffrage. His public rationale—or perhaps one that he thought would be palatable to his fellow politicians—was that suffrage would help America’s war effort.

In 1919, members of the House of Representatives and the Senate voted to pass the 19th Amendment, which was sent to all 48 states for ratification. Three-quarters of states were needed for the amendment to pass, and in the summer of 1920—with 35 states having voted to ratify the amendment, 36 needed overall, and several already having rejected it—the deciding vote landed on Tennessee. Back then, Tennessee was something of a swing state: It felt like the vote could have gone either way.

‘Be a Good Boy’

On August 18, 1920 the tension in downtown Nashville was palpable. Supporters and opponents of the amendment had set up separate camps at The Hermitage Hotel in Nashville, where anti-suffragists were holding forth on the proposed amendment in sexist and racist speeches.

Early in the day, Tennessee House members voted twice to table the ratification decision; both times they tied 48 to 48. The only option remaining was to vote on the amendment itself.

As the suffragists prepared to learn whether their fighting had paid off, many frantically counted the number of yellow roses affixed to the lapels of lawmakers. The flower had become a symbol of the cause. Those in opposition sported red roses.

One-by-one, in nail-biting succession, each member of the House declared his vote until the 49th vote, the deciding one, fell to Harry, who—at just 24—was the youngest state lawmaker. It was hard to miss the red rose on his lapel, an indicator—suffragists knew—could only really mean he was about to dash their hopes of changing history.

Harry hailed from a conservative district. He was under tremendous pressure to vote according to the wishes of his constituents, and these wishes largely did not include giving women the right to vote. But at the last minute, he changed his allegiance, casting his vote in support of the 19th Amendment. The crowd erupted. For the suffragists, it was indescribable relief at having won a bitter fight that had been raging longer than most of them had been alive. For the so-called antis, it was a cocktail of fear, anger and resentment. All agreed that after this moment America would never be the same.

'Hurrah and vote for suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt. Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt.'

Later, it became apparent that beneath that red rose, in his jacket pocket, Harry had been carrying a letter from his mother. “Hurrah and vote for suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt,” Febb had written to her son. “Don’t forget to be a good boy and help Mrs. Catt,” she wrote, referring to Carrie Chapman Catt, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

As Harry declared his historic “aye,” he reportedly dramatically ripped off the red rose, and the battle for women’s suffrage was over. He’d made his mother proud.

‘The Start of a New Fight’

When Tennessee became the “Perfect 36th”—the 36th state to ratify that all-important amendment—it marked a stupendous victory for some women. But by no means all women.

Although some Black women, particularly in the north and west, now had the right to vote, millions of women in the south were blocked from registering to vote by horrendous Jim Crow laws that legalized racial segregation.

Indeed, “for Black women, August 1920 wasn’t the culmination of a movement. It marked the start of a new fight,” wrote the professor and author Martha S. Jones in a Politico piece marking the centenary of the 19th Amendment’s passing.

Poll taxes, literacy tests, fraud and intimidation kept African American voters—both men and women—away from the polls. Many states also had so-called grandfather clauses that prevented the descendants of disenfranchised slaves, despite now being free, from voting. Although the Supreme Court struck this practice down in 1915, it wasn’t immediately eradicated everywhere. And Native Americans—both men and women—did not gain the right to vote until the Snyder Act of 1924.

So while some of the white suffragists triumphantly rested on their laurels, their nonwhite counterparts across America knew that the battle was far from over, and they also knew that they couldn’t necessarily rely on the existing suffrage groups for support. Many of them were racist.

“Black women moved forward alone,” wrote Jones in Politico. “They knew that their voting rights would fully arrive only with federal legislation that would override the states’ Jim Crow laws.” And that wouldn’t conclusively be until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Even today, as Jones notes in her piece, “Black women and men still face hurdles to voting.” According to research by the Brennan Center for Justice, a non-profit at New York University School of Law, the racial turnout gap—defined as the difference in the turnout rate between white and nonwhite voters—has steadily grown since 2012. “Restrictive voting laws generally limit the turnout of voters of color the most,” the researchers write. Examples of this restrictive legislation include laws that curb access to mail voting and laws that implement strict photo ID requirements for voter registration, according to the Brennan Center for Justice.

She Persisted

That critical vote ratifying the 19th Amendment that August day can’t be looked at in isolation. Decades of work led to that moment. Decades of work followed. Even today, the work is far from done. And while it’s true that Harry might get most of the credit, it took a passionate mother behind the scenes to shift the tide.

'I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.'

Like so many activists and suffragists through history—both forgotten and remembered—Febb Burn was fearless in her pursuit of what she considered to be fair. She persisted, and that’s noteworthy.

“She didn't attend any meetings or marches. She wasn't an activist as far as being involved, but she wanted the right to vote,” Tyler Boyd, Febb's great-great-grandson, told local news outlet Knox News in 2020. “She experienced how unjust it was and saw that she was able to make a difference.”

In a statement after the crucial 1920 vote, Harry aimed to explain his decision to his detractors. “I believe in full suffrage as a right,” he reportedly declared. “I believe we had a legal and moral right to ratify; I know that a mother’s advice is always safest for her boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification.”

Febb, meanwhile, told the Nashville Tennessean newspaper: “Some of my neighbors, I understand, have said they are sorry for me.” But—she added—“I don’t need any sympathy. I am proud of my son. He has covered himself with glory.”

And truly so had Febb. Her role in history—relatively small by some measure—was unequivocally critical, and she deserves widespread recognition and respect. Her name should be known far beyond the state lines of Tennessee. Febb Burn changed lives. How dare we forget hers.

Josie Cox is a journalist, author, broadcaster and public speaker. Her book, “WOMEN MONEY POWER: The Rise and Fall of Economic Equality,” was released in March.

Write to us at hello@thepersistent.com.