Why Can’t We Just Pass the ERA? It’s Complicated.

The Equal Rights Amendment is a simple 24-word piece of legislation. But it’s also a historic movement, more than a century in the making, that began with women’s suffrage and continues to this day.

Over the past few weeks, as equality advocates have called on President Joe Biden to use the final days of his presidency to publish the Equal Rights Amendment, many questions have been asked about the legal hurdles for ratification and what—despite a century-long fight—is still preventing gender equality from being enshrined in the United States Constitution.

Amid the chants, banners and bumper stickers, it’s important to remember that the ERA is so much more than a 24-word piece of proposed legislation. It’s a movement—years in the making, defined by grit, gumption and persistence—of 20th century feminism, of precedent-establishing court decisions, of women’s suffrage, and of individuals who dedicated their lives to making the U.S. a fairer place for all.

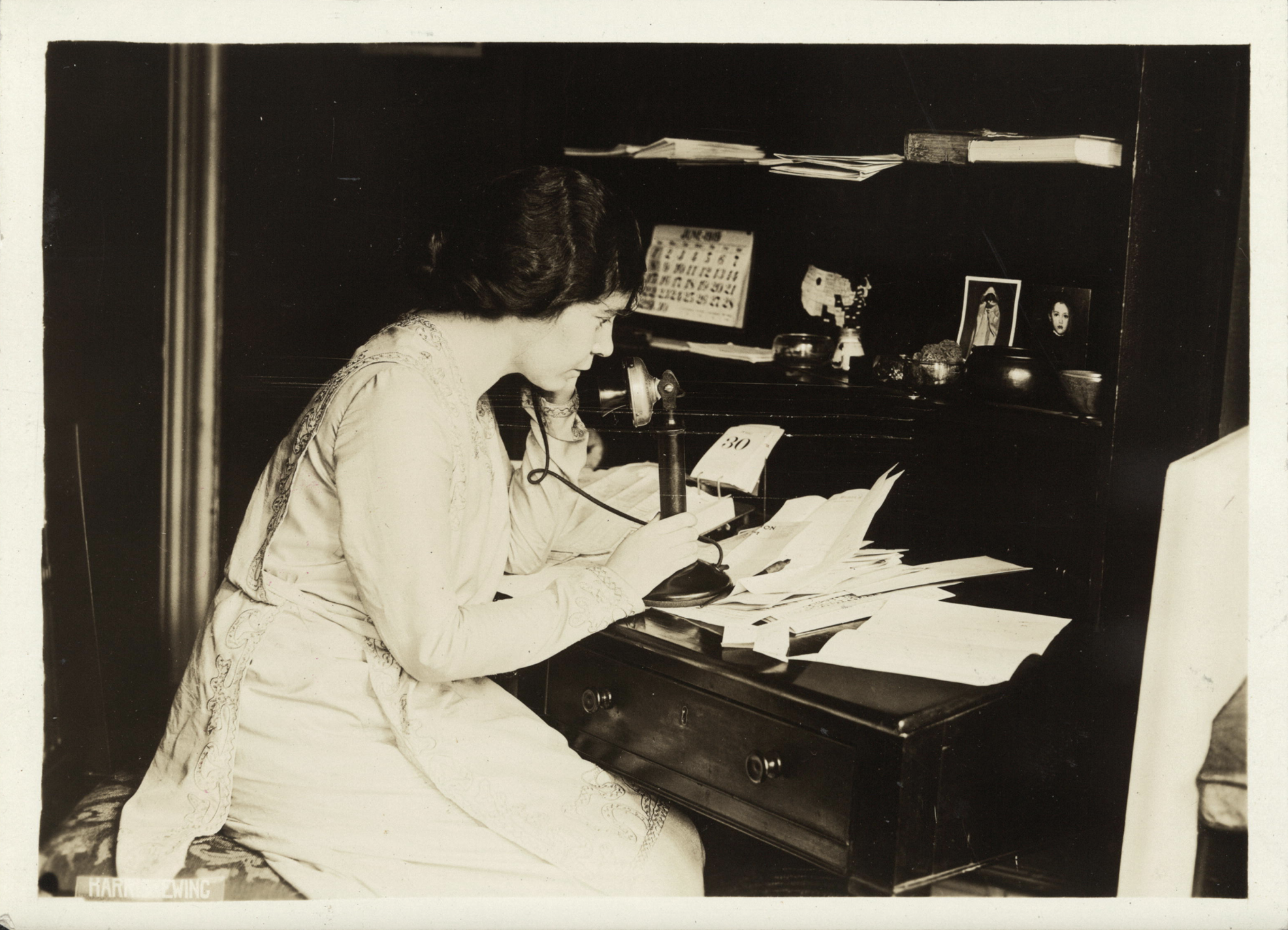

One such individual was Alice Paul.

Hello, Alice

Born in January 1885 in Burlington County, N.J., Paul was the first child of William and Tacie Paul, Quakers who raised their four children according to their faith’s staunch belief in gender equality. From an early age, Paul’s parents impressed upon their children that, regardless of gender, each had a duty to contribute to the betterment of society as a whole.

The Quaker belief in gender equality was unusual at the time, but helps to explain why so many of the individuals who were active in the fight for women’s suffrage were Quakers.

Paul attended a Quaker school in Moorestown, N.J., and then enrolled at Swarthmore College, a co-ed school (also unusual at the time), co-founded by her maternal grandfather. She excelled academically and was inspired by many of her teachers, including a mathematics professor named Susan Cunningham, who would later become one of the first women to be admitted to the precursor organization to the American Mathematical Society.

Lessons from Pankhurst

After her graduation, Paul moved to New York City, where she developed an interest in the emerging field of social work, learning about the detrimental effects of economic and gender disparities on communities. In 1907, she earned a Master’s degree from the University of Pennsylvania, where she studied political science, sociology and economics. Almost immediately after that, she moved to England, where a small group of militant suffragists was attracting media attention for resorting to violence to raise public awareness of their demands for equal rights.

There, she struck up a friendship with Christabel Pankhurst, the daughter of Emmeline Pankhurst—widely credited with leading the charge for women’s suffrage in the United Kingdom—and joined their movement. The women were regularly arrested for smashing windows and other acts of civil disobedience, which on several occasions landed them—including Paul—in prison. When that happened, they staged hunger strikes and were force-fed, which captured the attention of the media.

“The militant policy is bringing success,” Paul wrote of the strategy that Pankhurst and her fellow suffrage campaigners were using when she returned to the U.S. in 1910. “The agitation has brought England out of her lethargy, and women of England are now talking of the time when they will vote, instead of the time when their children will vote, as was the custom a year or two back,” she added.

Fighting for Suffrage in America

Upon her return to America, Paul re-enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania, this time in pursuit of a Ph.D. She also joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), formed in 1890 as a merger of two rival factions, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone, Henry Blackwell, and Julia Ward Howe. Soon Paul was appointed head of the group’s Congressional Committee, effectively putting her in charge of leading a federal suffrage movement.

In 1912, Paul moved to Washington, D.C., where she collaborated with other NAWSA members, including Lucy Burns and Crystal Eastman, to organize a massive women’s march for nationwide suffrage on March 3, 1913, the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Crowds of outraged onlookers, mostly men, heckled the thousands of parading women who’d traveled from across the country to be there. The march was swiftly brought to a violent end, but it drew extensive media coverage, alerting the public to the women’s demands and introducing the issue of voting rights into mainstream conversation and consciousness.

Paul had been working closely with NAWSA’s president Carrie Chapman Catt in the lead-up to the march, but as time went on, the differences in their political strategies and approaches became evident. Paul believed that pushing for constitutional change was more important than Catt’s focus on state campaigns. Their disagreement proved irreconcilable, and in 1914, Paul and a group of women who championed her strategy split from NAWSA and two years later established the National Woman’s Party (NWP).

‘How Long Must We Wait?’

Inspired by Pankhurst’s grit and willingness to throw physical and metaphorical rocks, the NWP in 1917 organized the first-ever public picketing in front of the White House. So-called Silent Sentinels bearing protest banners stood outside the gates of the White House to shame President Wilson for his inaction and apathy on the cause of women’s rights. NAWSA, as an organization, endorsed President Wilson, but Paul considered him and his fellow Democrats in power to be responsible for female disenfranchisement.

“Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?” one banner read.

Six days a week, irrespective of inclement weather, the women congregated in nonviolent protest. Quietly they stood in defiance of passersby who peppered them with half-hearted heckles and insults. At first, Wilson treated Paul and her fellow protestors with condescension or simply ignored them, but as the months drew on and the women persisted, tensions between the NWP and Wilson rose. When America entered World War I, a shift occurred.

The suffragists who, until that point, had been regarded by many as a nuisance at worst—pesky gadflies—suddenly drew wrath from members of the public who considered their actions to be entirely unacceptable and insultingly disloyal to the country. Angry mobs of mostly men started insulting them and during the summer of 1917, while they were still protesting non-violently, some of the women were arrested, purportedly for the crime of obstructing traffic.

As had happened in England, Paul was imprisoned later that year and, upon starting a hunger strike, she was force-fed. Well over a hundred women were arrested and kept in freezing, unsanitary, rat-infested cells. Paul ended up being moved to a sanatorium, where prison officials hoped she would be declared insane. Around that same time, however, information about the conditions under which the female prisoners were being held began to leak to the press. Appalled that anyone would be forced to live in such squalor, members of the public started to sympathize with the suffragists, demanding their release and exerting pressure on politicians to intervene.

When Paul was eventually released, she encountered a groundswell of support that was entirely new to her and that heaped pressure on President Wilson to seriously entertain the idea of supporting votes for women.

Finally, at the end of 1917, he did. In the subsequent months, Wilson met with members of Congress to drum up support for a suffrage amendment, presenting it as a “war measure.” The war, he claimed, couldn’t be fought effectively without female participation. In 1919, members of the House of Representatives and the Senate voted to pass the 19th Amendment, which was sent to the states for ratification. Three-quarters of states were needed for the amendment to pass, and in the summer of 1920, with 35 states having voted to ratify the amendment and 36 needed, the deciding vote landed on Tennessee.

In the end, it came down to a young man named Harry T. Burn who on the advice of his mother, declared his historic “aye” and the battle for women’s suffrage was over.

A New Chapter

After the enactment of the 19th Amendment, many suffragists turned away from activism and public life considering their work to be done.

Not Alice Paul.

Undeniable progress had been made in August 1920, but Paul knew that gender equality was far from guaranteed.

In the years that followed, she earned three law degrees at the American University in Washington, D.C., arming herself with the skills, experience, and reputation to craft legislation. In 1923, Paul announced that she had authored what she called the Lucretia Mott Amendment, in homage to the abolitionist she so admired. The amendment called for absolute gender equality and stated that “men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

Every year from 1923 until 1942, Paul and her supporters submitted the Lucretia Mott Amendment to Congress. It never passed. In 1943, with her patience running thin, Paul reworded the original draft to better reflect the language of the 15th and 19th Amendments, which she hoped would make it more palatable to lawmakers. The new version stated that “equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” It became known as the Alice Paul Amendment, and Paul continued to submit the revised version to Congress annually.