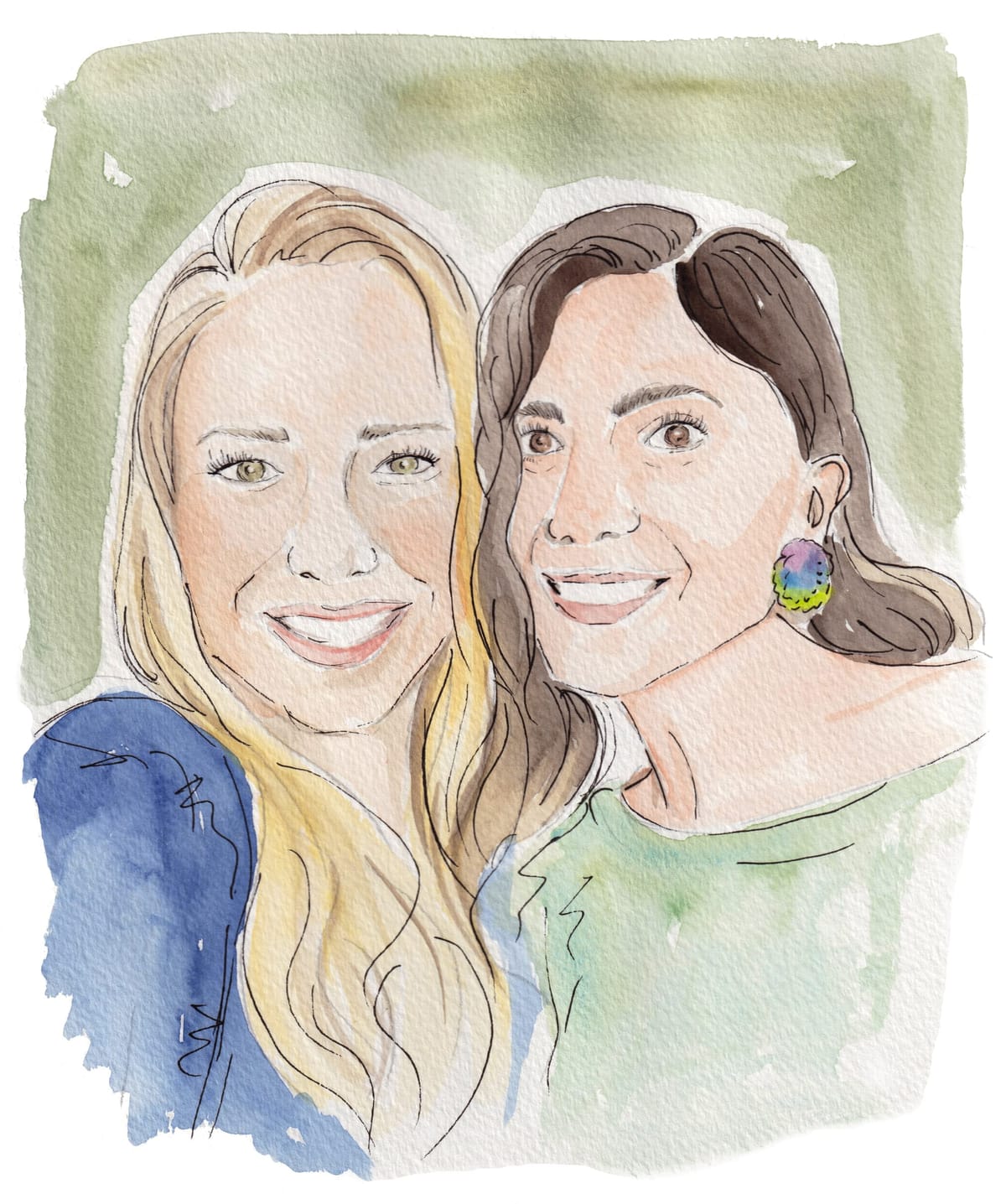

Two Friends, One Diagnosis: This Is a Love Story

When Kat Alexander started looping through cycles of mania, it was her best friend, Mara Altman, who came to the rescue.

Halfway through Kat Alexander’s fourth cycle of IVF, her best friend, the journalist Mara Altman (who has written for The Persistent), got a call from Kat’s fiancé, Dave. He needed help getting Kat out of the house to a medical appointment.

“I didn’t understand why he needed help,” says Mara. But when Mara arrived at Kat’s California home, it became clear. She kept taking off her clothes, darting from room to room, and saying she was the John Oliver of computer programming.

Kat was experiencing a manic episode.

Over the following months, it would become a lot worse and ultimately result in a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Sometimes she seemed lucid; other times, it was hard for people around Kat to understand what was happening to her.

At one point, Kat claimed she was starting a “billion-dollar business” to help domestic violence victims recover. She took one such person to a high-end hotel and showered her with gifts. Kat blew through her savings, spending thousands of dollars on luxury items like purses, activewear, silk scarves and leather wallets. She believed she was a “conduit for money, it was meant to flow through me and out to others,” she explained later on. Needless to say, she isolated herself from friends and her fiancé in the process.

Kat disappeared, reappeared, rammed her car repeatedly into a parked car outside an Airbnb she had been staying in, and sent Mara—who had been her closest friend since just after college—expletive-laden messages telling her to check her privilege, explaining that Mara and their other friends must work to earn Kat’s friendship back.

There were many hospitalizations. Sometimes the police brought Kat in. Sometimes it was Dave. The visits lasted about three days—enough time for her to stabilize on antipsychotics, after which she’d be allowed out. Once released, the mania would ramp right back up. The looping cycle would continue despite Kat being prescribed medications.

Finally, after one extended hospital visit and about 10 months of depression, Kat took off to Playa del Carmen, a tourist town in Yucatan, Mexico, to attend an ex-boyfriend’s wedding. She found various reasons not to return home to California until two weeks after the wedding, Kat disappeared altogether.

At this point, Mara and Dave called the U.S. Consulate and began scouring social media. It was social media that provided clues: “Someone said they thought they saw her alone and disheveled, with her suitcase,” explains Mara. ”Another person said she’d tried to attack him on the street.” Eventually, Mara was sent a video of Kat on a street in Playa del Carmen, directing traffic, flashing people in a small tank top and wearing bikini bottoms.

And that’s when Mara—not Dave, who Kat, in her psychosis, regarded as “dangerous”—got on a plane to attempt a rescue.

Two years on, with Kat now in a more stable place and back home living with Dave, Mara and Kat have released an audiobook “Episodes: The True Story of Two Friends & One Diagnosis.”

The narrative flips back and forth between their perspectives as they tell their story—Mara talking about watching her friend become overwhelmed by her mania; Kat explaining how she rationalized her actions to herself. Snippets of audio recorded in the moment and messages Kat recorded for Mara during her most manic moments are layered in. The result is an extraordinarily compelling story of female friendship and healing.

It also offers insight into how profoundly mental illness can quickly grind life, progress, family, career to a halt—Kat had been developing a wellness program for the San Diego Unified School District when all this happened.

In an interview with The Persistent, Kat and Mara explain why they created "Episodes," what they hope their listeners will get out of it—and why, ultimately, their tale is a love story.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.