As the Trial of ‘Mr. Every Man’ Draws to a Close, France Debates ‘Intent’ vs. ‘Consent’

The Pelicot trial pits the notion of intent against the concept of consent. The outcome could alter how these kinds of cases are handled in the future.

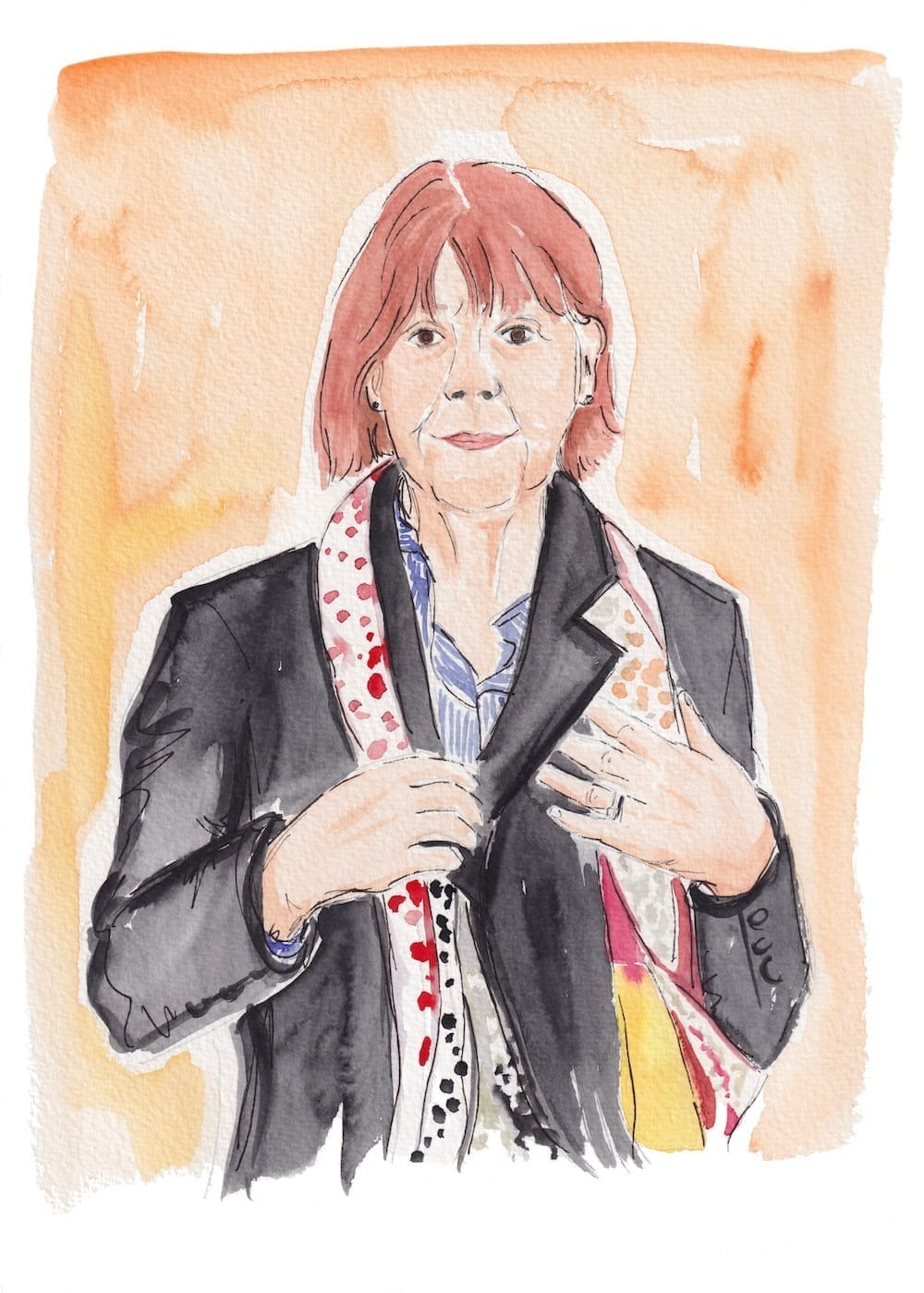

Every day for the last four months, Gisèle Pelicot, 72, has emerged from the courthouse in Avignon, France, to a cheering crowd of almost all women. Usually someone will hand her a bouquet. Choirs have sung for her. Women have marched for her. People from all corners of the globe have sent her letters and gifts.

The sleek modernist courthouse sits directly across a wide street from the medieval ramparts of Avignon and, since early September, has been the site of a historic trial in which 50 men stand accused of sexually assaulting Gisèle Pelicot, while she was drugged and unconscious. The men had taken part in the assaults at the urging of Pelicot’s husband, Dominique Pelicot, also aged 72.

Dominique Pelicot has already admitted to the facts of the case: Over the course of a decade, he crushed anti-anxiety medication and sleeping pills and slipped them into his wife’s food. After she had passed out, he invited men he’d met in internet chatrooms to rape her in the Pelicots’ marital bed. Often he filmed the scene; sometimes he joined in.

The videos, which were found on Dominique Pelicot’s devices and routinely shown as evidence in court, are profoundly disturbing, almost unwatchable.

As for the men, they are largely unremarkable. Among them are a firefighter, a nurse, a journalist, a prison warden, a soldier, farm workers, and truck drivers. Their ages range from 26 to 74. They are fathers and husbands. “Mr. Every Man” the media dubbed them.

And then there is Dominique Pelicot himself, a retired electrician and avid cyclist. His children thought he was a great father and grandfather, his wife often remarked to herself how lucky she was to have him.

The lurid details of the case have captivated France but the trial has also sparked a national conversation about the very definition of rape. The arguments presented in the courtroom have pitted the notion of intent—does a person have to expressly intend to rape for a sex act to qualify as a crime—against the concept of consent. And on the latter point of consent, must it be expressly given? Or can it be assumed or given by proxy? Indeed, is it even required?

The outcome of this trial could alter how rape cases are handled by France in the future. It could result in a rewriting of the legal code. So far, the proceedings have already called into question how rape victims are treated by the French legal system and challenged a widespread culture of misogyny.