Lee and Me

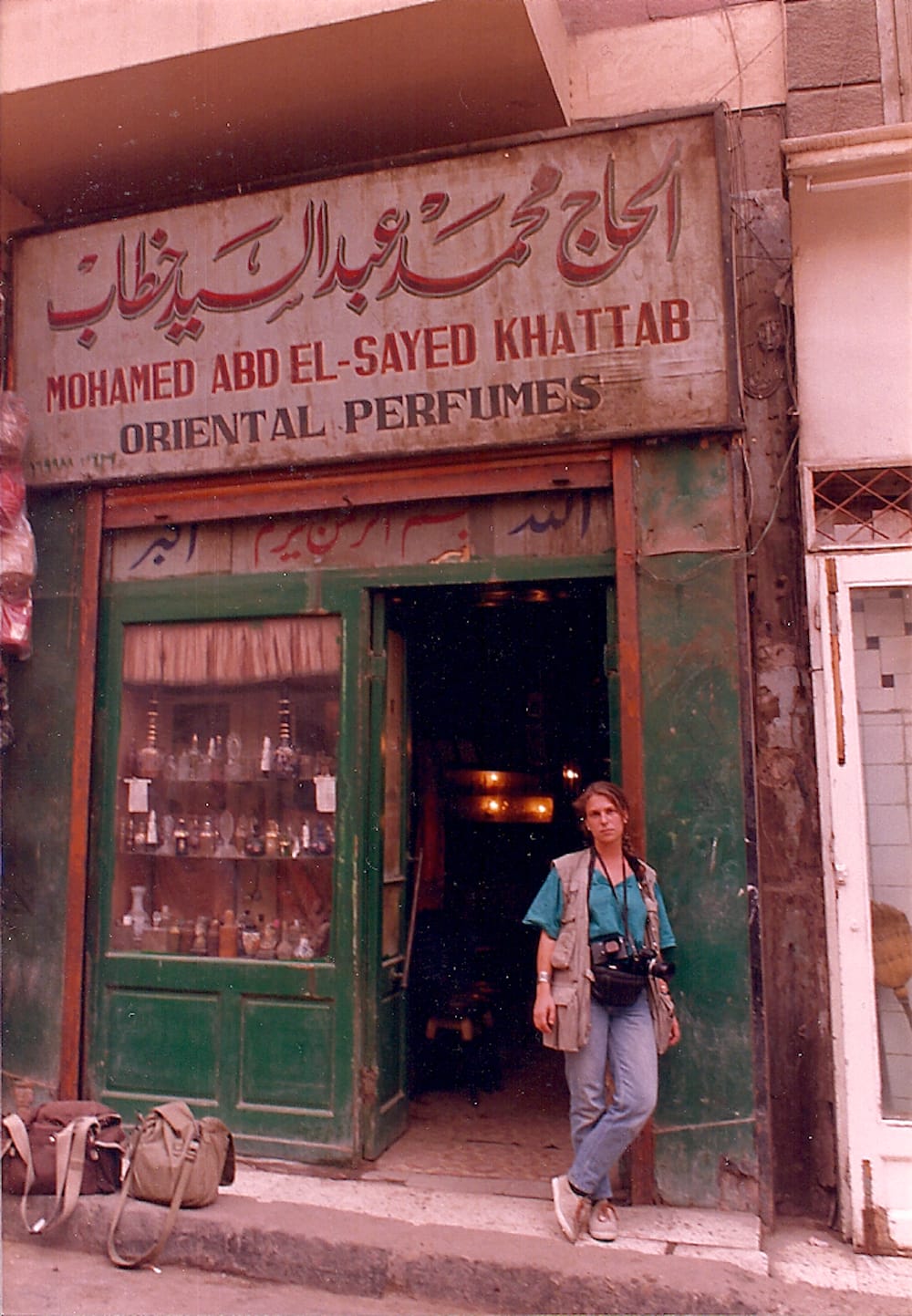

I wanted to be the objectifier of men and their wars, quirks, and shortcomings, not the objectified. Why was this so hard?

The Persistent is available as a newsletter. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

When I heard that it took nine years for Kate Winslet to turn Lee Miller’s life as a war photographer into Lee, her latest film, I was less shocked by the length of time it took and more by the fact that she was able to get it made at all. Particularly since Kate (*See Writer's Note) insisted on viewing Lee the way Lee viewed the world—flaws and all, through a female lens, using female collaborators. Which—how shall I put this?—is not, in my experience, how these things are done.

Lee was born in Poughkeepsie, N.Y., in 1907. She moved to Paris as a young woman, and began her career as a fashion model and muse to artists such as Man Ray and Picasso. She then became, in her late 30s, a pioneer in the field of female war photographers as well as a hero—along with the likes of Margaret Bourke-White and Gerda Taro—to those of us who followed in their footsteps. Lee was one of the first photographers, female or male, to document the horrors of Dachau. She was able to pursue this line of work—and for Vogue, unbelievably, at that—because Audrey Withers, then editor-in-chief of British Vogue, not only encouraged Lee but, critically, funded her work in Great Britain, France, and Germany during World War II.

Kate, too, had a team of female collaborators to back up her vision: her co-producer (and co-Kate), Kate Solomon; screenwriters Liz Hannah and Marion Hume; and director Ellen Kuras, the brilliant cinematographer she met on the set of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, who has shot dozens of well-respected films but—I had to fact check this twice—is only now making her feature film directorial debut with Lee (and FFS, Hollywood, may it lead to many more).

Oh, and get this: When the film’s budget ran out during two critical weeks of filming, Kate Winslet, who was badly injured on set when she slipped and fell on her coccyx in a rehearsal, paid the cast and crew’s salaries out of her own pocket and did not miss a single day of work.

If you haven’t yet seen Lee, I urge you to run to your nearest movie theater and do so, if only to let Hollywood know that, yes, we want and need more films like this.

If you haven’t yet seen Lee, I urge you to run to your nearest movie theater and do so, if only to let Hollywood know that, yes, we want and need more films like this—in which the lead actress wields both power and a camera, but also is not afraid to appear on screen barefaced and un-botoxed, scraggly-haired and curvy-bodied. Hers is a role that presents woman as we actually are—complicated characters with agency, depth, contradictions, and flaws—and not as anodyne sex objects to be acted upon by others.

“I think we live in a time now where we are starting to see actresses play parts that are redefining what it means to be feminine,” Kate said recently. “Femininity is different now. Femininity isn't a flowery dress and a tiny little figure and a full face of makeup. Femininity is resilience and courage and power and passion and sisterhood and standing up for oneself. And for me that's who Lee Miller was.”