Remembering Lilly Ledbetter: A Life of Grit and Persistence

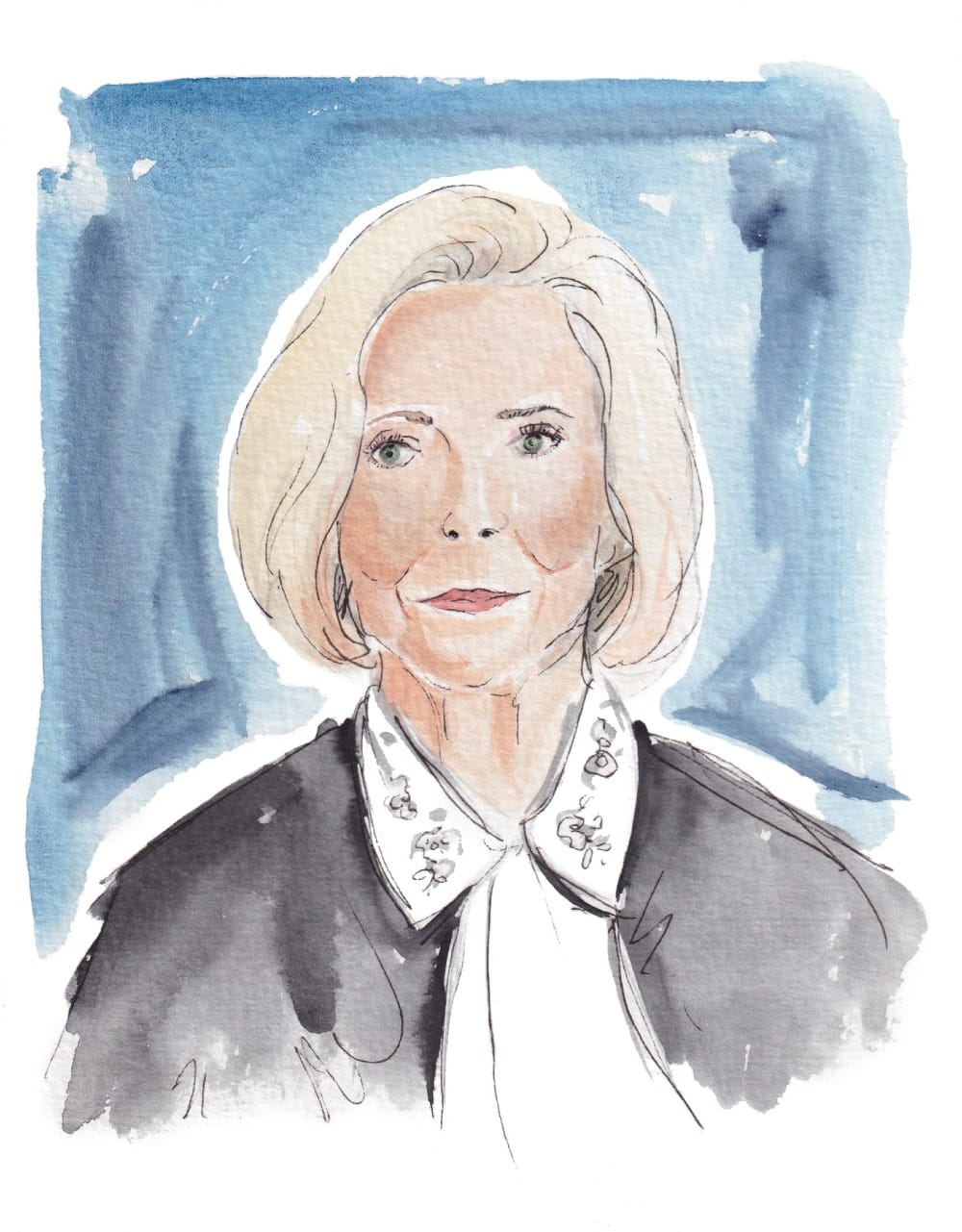

Lilly Ledbetter, for whom America’s Fair Pay Act of 2009 was named, has died. She was 86.

One morning last May, I woke up to a barrage of well wishes. It was my birthday. The messages were all lovely, but one stood apart from the pack.

“Greetings Josie,” it began. I glanced down to the end. It was signed, Phillip from Palm Beach, Fla.

He was writing to let me know that he’d bought a copy of my book—Women Money Power, a narrative history of women’s economic empowerment—for his mother as an early Mother’s Day gift. “She loved it,” he informed me.

Hearing from any reader who loves my book thrills me, but this was different. Phillip’s mother was Lilly Ledbetter, one of America’s most ardent equal pay advocates—the namesake of a historic piece of legislation aimed at protecting workers from pay discrimination, signed into law in 2009 by Barack Obama.

Over the years—both in my journalism work and as a book author—I’d put in half a dozen requests to interview Lilly. None had been successful. But now I was learning that she, a personal hero of mine, had not only read my book—“cover to cover,” in Phillip’s words—but also loved it.

A few days later, Lilly herself got in touch over email. She praised my writing and the way I’d covered her complex and drawn-out pay discrimination case. “Only a few [books] I have read cover [the] case as completely as you did with mine, which is very important,” she wrote. And then, a request: “My book is not signed, so I will look forward to receiving a signed copy.”

Of course, I obliged immediately, penning a long hand-written note on the inside cover. “Your courage and selflessness—your endurance and, of course, your grit—make you a hero upon whose shoulders we all stand,” I wrote.

On Saturday evening, Oct. 12, 2024, Lilly passed away peacefully, surrounded by those who knew her best and loved her most, including her son Phillip. She was 86. She lived ferociously and fearlessly—a fighter until the very end.

When I heard the news, I was crushed: The world had lost a trailblazer, someone who was truly selfless in her pursuit of justice. But I am also filled with hope that her passing will reignite the Lilly Ledbetter story. In my view, it is a story worth telling and re-telling.

‘A Missionary in a Strange Land’

Most stories about Lilly begin with the stirring account of that day in March 1998 when she turned up to her shift as a supervisor at the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company plant in Gadsden, Ala., to find a note in her mailbox.

On a torn piece of paper, an anonymous author had scribbled four names in black ink: Lilly’s, followed by the names of three of her male co-workers. All four had the same seniority at the plant—their job titles were close to identical.

Next to Lilly’s name the author had written a number: $3,727. Even in her state of confusion, Lilly immediately recognized it as her monthly salary, accurate down to the dollar. The numbers listed next to the other names ranged from $4,286 to $5,236. The implication was clear: She wasn’t just being paid less than her male colleagues, her salary was significantly smaller, a difference that would have amounted to a life-changing sum over the course of an entire career, had she been paid it.

It was the first step in what would be Lilly’s more than decade-long legal journey that would include the filing, then fighting, of her lawsuit in courts across the country; that would bring her all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court; make her the foundation for a piece of legislation in her name; and, naturally, place her in the annals of U.S. history.

But Lilly’s story, the origins of her discontent and the genesis of her courage to fight big business, started long before all that.