The Real Losers of the Paris Olympics Are the Stereotypes That Hold Women Back

Athletes at the Paris Olympics have challenged perceptions of what it means to be a woman in sport.

In just over a week, the Paris Olympics will be history. Over 10,000 athletes will have duked it out across 32 different sports. Careers will have been made and crushed; records broken and missed; epic comebacks—from Celine Dion to Sunisa Lee—met with unbridled tears of joy.

The games will be remembered for many things—bad and good: A chilling arson attack on France’s high-speed train network just hours before the opening ceremony; a heat wave that threatened to imperil the health and wellbeing of both participants and spectators; and—of course—a (mostly) successful campaign to make the 2024 Olympics the most gender equal in history.

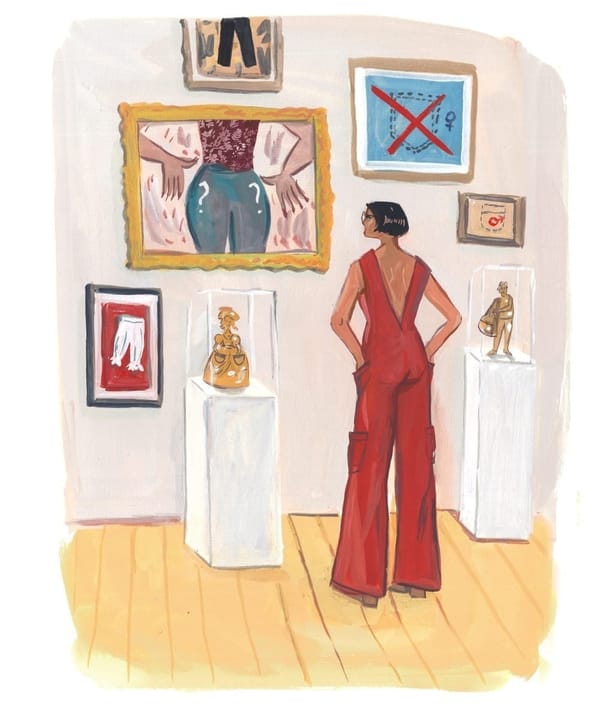

When future generations look back upon 2024’s summer of sport, however, they will hopefully also acknowledge something else—something less obvious. While true gender equality may yet be somewhat fanciful, something has shifted.

In Paris, the woman athlete is showing up in ways that are breaking stubborn, centuries-old stereotypes. The cracks are subtle for now, but the mold is definitely coming apart. And that means that even a defeat in competition is a win for a more gender equal society across sport and beyond. Sure, it’s a long game, but the signs are promising.