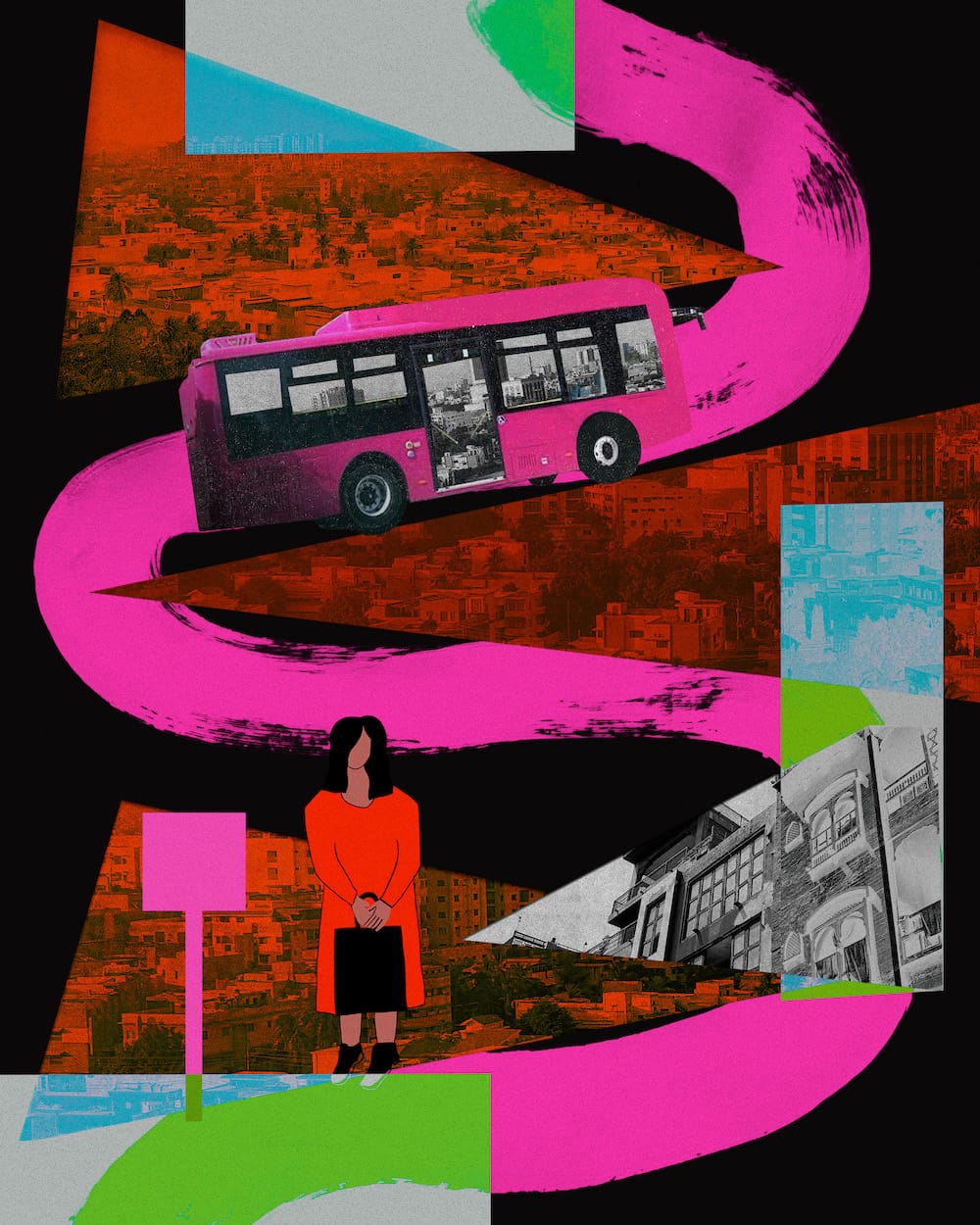

Inside Karachi’s Women-Only Pink Bus

A new women-only bus route is designed to combat the sexual harassment prevalent on Karachi’s public transit system. The bus is clean, spacious—and unreliable.

On a bright Tuesday morning in June, I found myself waiting at the Numaish Chowrangi bus station in downtown Karachi. Crowds thronged past me, racing to catch their buses in and out of the city. More passengers crowded in, weighed down with packages and luggage.

Meanwhile I waited. And waited. And waited.

I was here for route 10—specifically, the “Pink Bus” on that route, a service for women passengers only.

Launched in February 2023, the Pink Bus runs on five of Karachi’s busiest routes. The project, which cost a total of 12 billion Pakistani rupees (roughly $43,000) is government-funded. It started with three routes and 18 buses, each painted a bright, Barbie pink. In April of this year, it added another two routes and 10 more buses.

The service was badly needed. According to a 2014 survey, 85% of working women, 82% of students and 67% of homemakers had felt harassed at least once in the previous year while commuting on Karachi public transport. The perpetrators were found to be fellow passengers (75%), conductors (20%), and sometimes even the bus driver (5%).

Not much has changed. And despite the continued high instances of harassment, reporting it is almost impossible: The only way for women to complain or reach out for help is through social media. And while there have long been women-designated sections on buses, the harassment still happens.

For many women in Karachi, the harassment on public transport is so problematic that they simply don’t travel. That, coupled with Pakistan’s cultural barriers around women interacting with men, is a key factor keeping women out of the country’s workforce. (Just 21% of Pakistan's workers are women.)

The 2014 survey showed that 40% of female students restricted their travel after sunset due to harassment, which reduced their mobility. Cars are prohibitively expensive for most low-income households, and while motorbikes are slightly more affordable, there’s also a much lower social acceptability of women riding motorbikes—although that, too, is slowly being challenged.

Credit for the Pink Bus may go to male politicians like Sharjeel Memon, the minister for transport in Sindh, the province that includes Karachi, but the broader program is run day-to-day by the gender specialist and research analyst Huma Ashar.

Having a woman in this role is important, notes Marium Naveed whose work focuses on urban public spaces and public transportation. “When women are at the table where these decisions are being taken, that's where you really ensure that top to bottom, you’ve thought this through,” she says.

A quick fix is not a solution

Ishrat Jabeen, a gender specialist for Pakistan at the Asian Development Bank, whose work has included projects in the transport sector, notes that without actively tailoring the services to women’s needs—such as having bus routes near schools and creating a safe environment at bus stops, or offering micro-mobility options like women-friendly rickshaws or walking routes to get to and from those bus stops—the Pink Bus could end up being the equivalent of “creating a well without access to water.”

While Jabeen appreciates the initial step in launching the Pink Bus, she points out that all of these factors need to be taken into account for it to really benefit women in the long run.

The reality is that it’s far from perfect. Online information about the bus is scant, and when I ask a traffic policeman, he tells me that sometimes the Pink Bus doesn’t come for three hours. (Officially, it is meant to run from 7 a.m. to 8 p.m.). Also, the drivers are still men. Women have been trained to take up driving the Pink Buses, but the analyst Ashar says they won’t start until 2025.