The Compelling Case for Careful Self-Promotion

Women are told to lean in and dare to lead, to be a girlboss and to speak up. But nothing is easy about this. And none of it is risk-free.

The Persistent is available as a newsletter. Sign up here to get it delivered to your inbox.

An excellent piece of advice I got from an author friend before I published my book earlier this year, was never to read the reader reviews. “The internet is nasty,” he warned me. “Don’t do it.” And so I didn’t. Until—inevitably—I did.

To the surprise of absolutely no one, including myself, it turns out my author friend was very, very right. A prodigious number of comments came from that army of faceless armchair critics spewing bilious, vile and personal remarks. Some were snidely mean. Some were baseless. Many were just plain ill-informed. I’m convinced many of these so-called critics had never laid eyes upon my book, let alone read it.

Did anyone, anywhere have anything nice to say? No doubt they probably did, but I wasn't seeing it thanks to negativity bias (the idea that our brains are hardwired to dwell more on the negative than the positive).

Until I was.

“This shit was actually fire,” a comment began on Goodreads, and then went on in the same vein. “I loved how the book was a timeline, it gave me every little bit of info and context I needed.”

I was stunned. I was thrilled. But I was also bewildered.

Unsure of how to process all of this pride and disbelief—a caressed ego, but also a weird twinge of something akin to shame for experiencing all of those nice things—I wrote to my editor (Hi, FD!).

“Can I brag for a second about one tiny thing?” I Slacked her, impulsively.

“OMG. YESSSSS. 👂” she wrote back.

And thus began my journey into the fascinating and infuriating world of self-promotion, humblebrags, “boomerasks” and, yes, a healthy dose of sexist cultural norms. This is the real world, after all.

A Delicate Balance

When it comes to being successful at work, one of the toughest challenges relates to cracking “the confidence code,” something that the journalists Katty Kay and Claire Shipman describe as “the science and art of self-assurance” in their eponymous book.

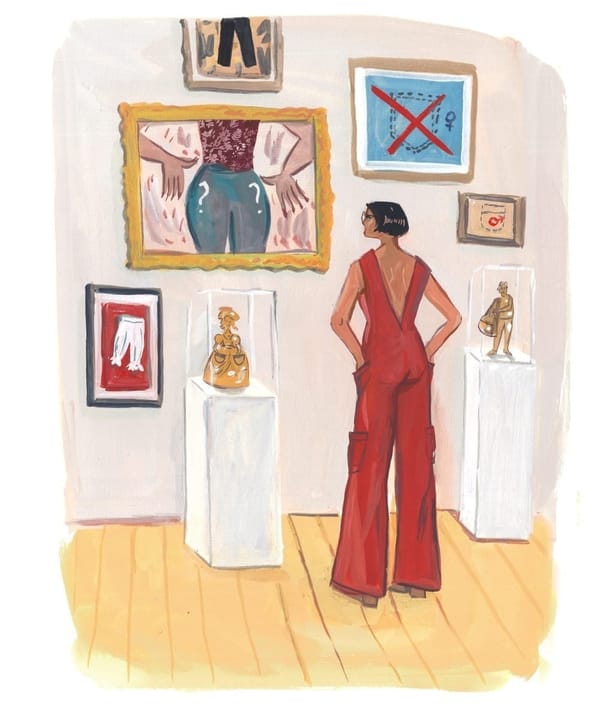

Over the decades, women have been instructed to lean in and to dare to lead—to be a girlboss and to speak up. All of this also means embracing opportunities to self-promote and to be your own most ardent champion; to highlight your competence whenever possible.

But absolutely nothing is easy about this. And absolutely nothing is risk-free.

Remember the paradox of female success that America Ferrera’s character Gloria so explosively details in the Greta Gerwig’s Barbie movie? It’s a zinger of a speech, bemoaning the fact that “you have to be a boss, but you can't be mean.” That you have to lead, “but you can't squash other people's ideas.” That you have to “always stand out” but also “never show off, never be selfish, never fall down, never fail, never show fear, never get out of line.”

This is rarely more relevant than when a woman is trying—deservedly, of course—to highlight her brilliance while avoiding the perception of arrogance. It’s a balance that’s so hard to strike, and frankly so exhausting, that many just don’t bother.

“I know I’m good at my job, and that’s enough for me,” the collective thinking might go. But the gender bragging gap (I know, I know, I’m bored by this gender-whatever-gap construct too) is real. It’s not going away, and it’s worth exploring its prohibitive and enduring costs.