Was Shakespeare a Feminist? Juliet Gives Us a Clue.

A new production of Romeo and Juliet in London peels back layers of misogyny, racism and sexism. It’s a lot.

The news earlier this year that Romeo and Juliet would have a 12-week run at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London started out auspiciously, but quickly turned sour.

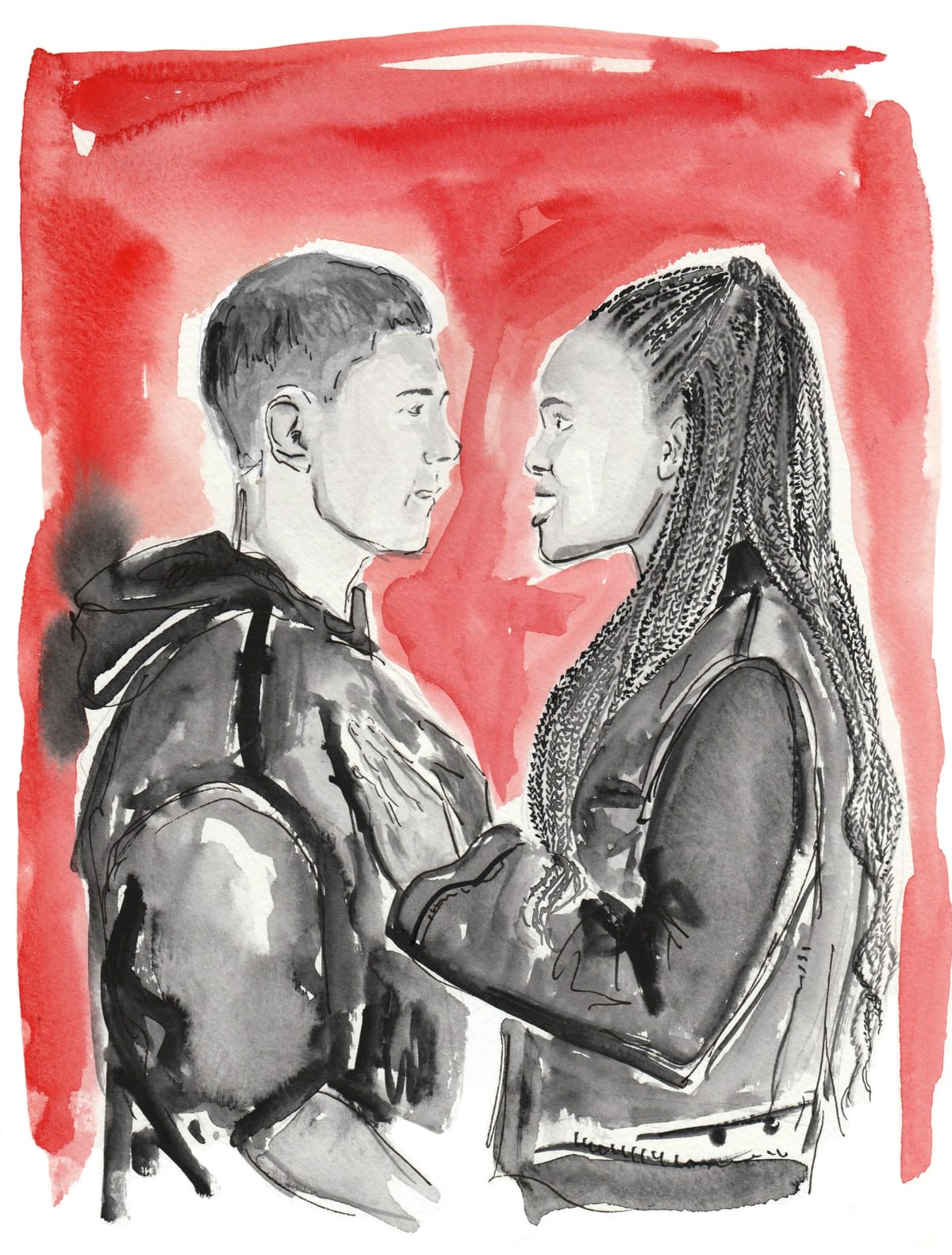

Fans celebrated the casting of Tom Holland (of Spider-Man fame) in the role of Romeo, and tickets for the run sold out within hours. But a torrent of online racist abuse was also directed at Francesca Amewudah-Rivers playing Juliet because Juliet—who is a fictional character and supposed to be 13—the trolls argued, is not traditionally Black.

Excuse me?

(If you’re detecting a parallel with the time that Halle Bailey’s casting in the title role of The Little Mermaid drew criticism because Ariel—who is a fictional character—isn’t traditionally Black; well, yes.)

The Jamie Lloyd Company, the production company behind this staging of Romeo and Juliet, put out a notice condemning the barrage of “deplorable racial abuse,” on X and its Instagram feed (the bio for which proudly declares Holland will play Romeo and…does not mention Amewudah-Rivers at all. Last I checked there’s no Romeo without Juliet, but I digress.)

Meanwhile over 800 Black actors signed a letter of solidarity calling out the racist and misogynistic abuse.

It was against this backdrop that Juliet—played by the unequivocally excellent Amewudah-Rivers—would step onto the stage. For the story of a young woman buffeted this way and that by the lowest human instincts, it felt very on point. Off I went to see it for myself.

I must admit, some years have passed since I last pored over the text of Romeo and Juliet. It's a love story, sure; some teenage angst; a pile-up of bodies. But it took this production to peel back the sheer monstrosity of what Juliet endures.

Read more: The Rebellious Power of the Statement Tee