Below the Surface of Women’s Art, Centuries of #MeToo, Misogyny

Viewers who take the time to look closely at Tate Britain's "Now You See Us" will uncover a great deal about the plight of professional women artists over the last 400 years.

Can an assemblage of polite portraits, sentimental botanical prints, and charming “needlepainting” say something new about women’s efforts to be taken seriously as artists?

An exhibition at London’s Tate Britain, Now You See Us: Women Artists in Britain 1520-1920, aspires to do just that, showcasing 200 works by women who forged artistic careers in spite of the societal expectations of their time.

Curators have indeed gathered some fascinating works, but—dare we say it—is the theme a little done?

Enough to create change?

A woman's group show is hardly a new idea, or in itself a very compelling one. The first all-female international art exhibition was held almost half a century ago, in 1976, and since then curators have been recycling this premise with little variation. The forgotten women, the overlooked women, the erased women—we’ve heard it all before. Even Linda Nochlin, the feminist scholar who wrote the foundational 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” suggested in her writing that merely showing more examples of works by under-appreciated women—technically superior though they may be—isn’t enough to create change.

But the Tate insists that the appetite for such a show is healthy as ever. “You only need to look at the popularity of other shows of women artists around the world, as well as the explosion of books, podcasts and articles around the subject, to see that there's a high level of interest in revisiting what we think we know about women artists of the past,” explains Tabitha Barber, the museum’s curator of British art, 1500–1750, in an interview with The Persistent.

Barber adds that the impressive attendance records for the Tate’s recent blockbuster show, Women in Revolt! Art, Activism and the Women’s movement in the UK 1970–1990, indicate the public’s enthusiasm for the subject. But the appeal of Now You See Us is more subtle.

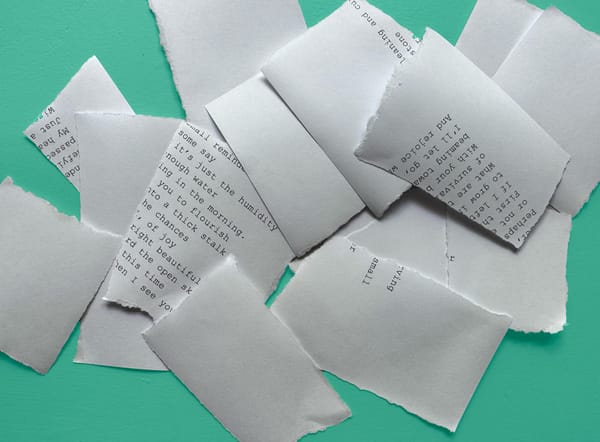

In lieu of radical (and Instagrammable) feminist art, we have traditional works that invite viewers to pause, to linger, to probe a little. The reward is a journey beyond the often-polite compositions that invites the viewer to question, well, everything. This isn’t a simple ask at a time when the typical museum visitor spends less than 30 seconds looking at a work of art.

Those who do take the time to look closer at Now You See Us will uncover a great deal about the plight of professional women artists over the last 400 years.