Providing Care After Roe, These Doctors Met a Hurdle They Didn’t Expect

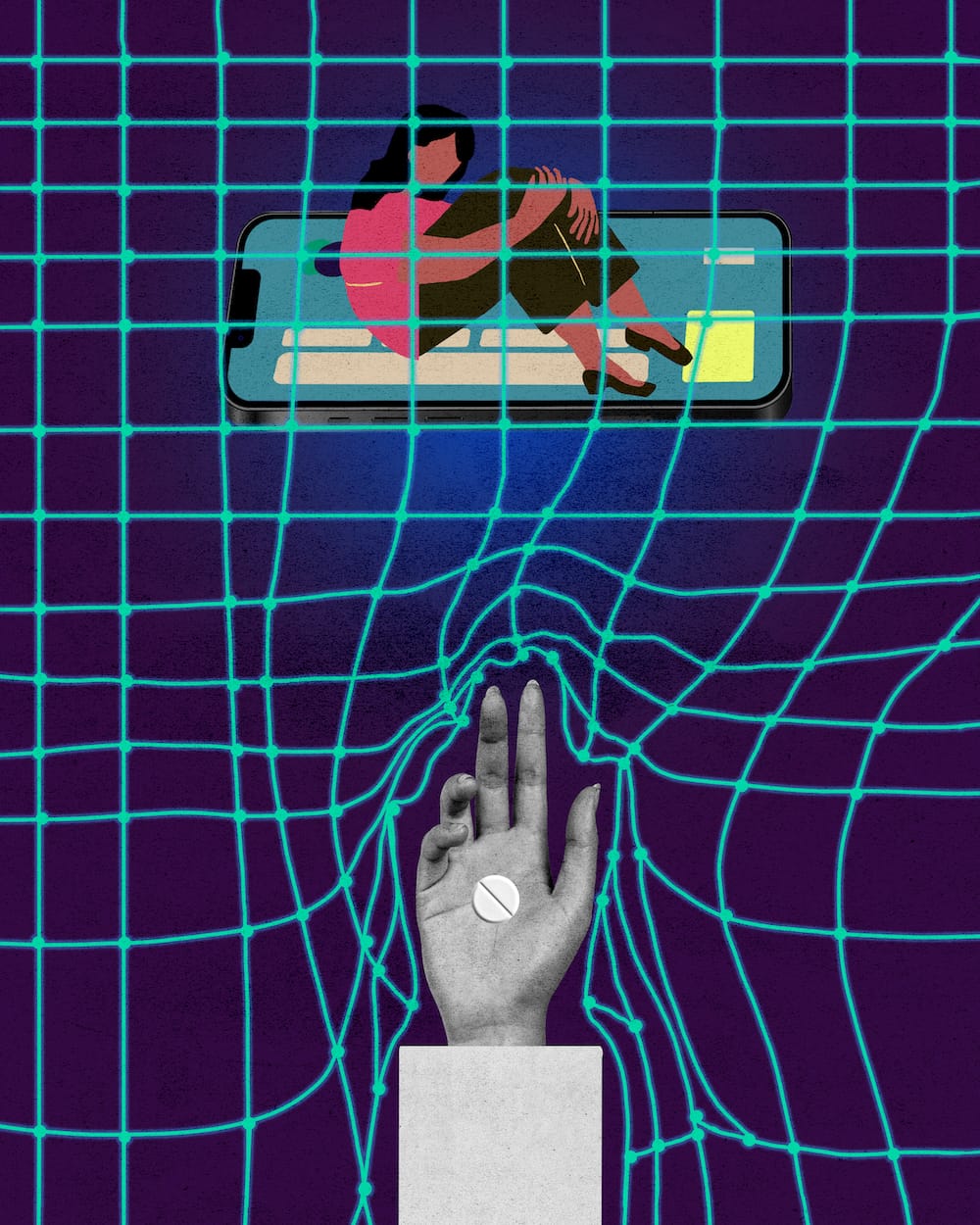

Online abortion providers face constant headwinds, even with protections and systems in place.

One chilly morning last December, Rose, a family medicine doctor who lives in the northeast of the U.S., woke up to an inconvenient surprise: She’d been booted off Square, the online payments platform.

For many this might seem like a simple annoyance. For Rose it was much more consequential.

For nearly six months, Rose, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, had been prescribing and mailing abortion pills to patients across the country, predominantly to individuals in states with severe restrictions—or outright bans—on abortion. She handles all her patient payments through a combination of online payment processors, like Square. Without them, she can’t get paid, and if she can’t get paid, that will bring her caseload of online abortion services—which can comfortably exceed a thousand a month—to a grinding halt.

Rose is one of just over a dozen U.S. healthcare providers leveraging so-called telemedicine shield laws—legislation that has come into effect largely in response to Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the landmark 2022 Supreme Court decision that bulldozed a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion in the U.S.

The shield laws, which have so far—starting in 2022—been enacted in eight Democratic-led states, are designed to explicitly protect licensed doctors, nurse practitioners and midwives who are prescribing and sending abortion pills to patients in other areas of the country where abortion access is deeply restricted or under threat.

Ever since Rose started sending pills to patients in states including Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas, she’s known that she’s a pawn in a battle between those who think women should be able to end a pregnancy via mailed pills and those who don’t. The obstacles to providing care in a field of medicine that’s become a monumental political battleground are well-established. As of August, more than 20 states have banned abortion outright, or have enforced severe restrictions on the procedure. What’s unexpected, though, are the significant headwinds stemming from the tech sector.

She knows she’s a pawn in a battle between those who think women should be able to end a pregnancy via mailed pills and those who don’t.

Rose says that when Square booted her from the platform it did so overnight and without warning. A spokesperson for Square, when contacted by The Persistent, said, per its terms and conditions, the platform does not support so-called “card-not-present payments for any type of medication or pharmaceuticals”—which include online, mail order or telephone orders.

This makes sense to Rose, but what she doesn’t understand is why at first she was able to use the platform and then suddenly she wasn’t; it’s a flip-flop that has seriously curtailed her ability to do her work.